Linear Regression

This post dicusses how to come up with linear regression algorithm, specifically how to define the loss function and minimize the loss with gradient decent algorithm. I also implement the linear regression using Python (numpy) to do experiment with a datasets, and the result can be found in this IPython notebook.

1. Problem setting

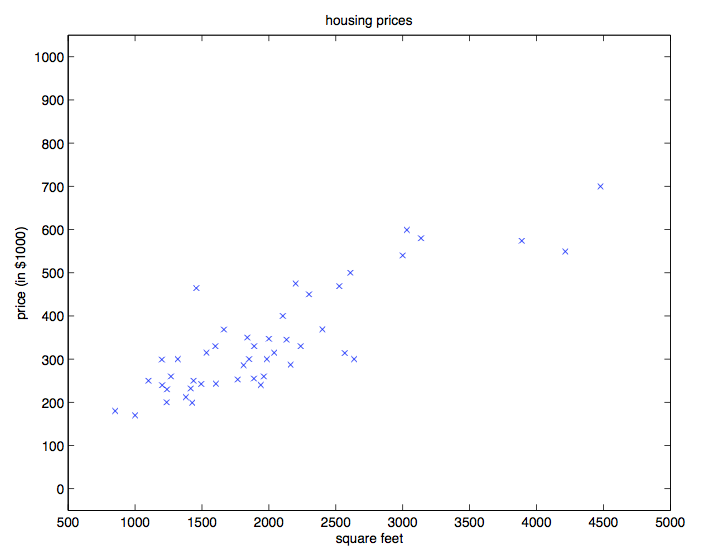

We want to use a predictor variable X to predict a quantitative response Y, such as using living area (X) to predict the price (Y) of house.

2. Basic idea

Becuase of just two variables, we can simply visualize the data on a scatter plot, then we can predict Y by the structure of the plot (see following figure)

After getting the scatter plot, we can estimate the position of potiential point when given the x value and get the corresponding value y.

3. Can we do better

So far it seems that the problem can be solved, however, we shold always ask the quesion, i.e., “Can we do better?”

What’s the shortcoming of the above solution?

- We have to firstly get the scatter plot, which is a problem when it scales to high dimension prediction problems.

- We need our human’s eyes to find the position of the position of potential point. We humans are not happy with that, instead we want the computer to do all the work. In addition, we can easily get overwhelmed when amounts of prediction needed.

4. Better idea

If we look at the structure of the scatter plot above, it is not hard to figure that the Y value is increasing when X gets bigger. So it is possible to find a model to fit all the data, then use the model instead for prediction.

Then what’s kind of model we should use? Linear model may be a good choice because of its simplicity and ability to show the general trend.

The next task is how to find the “best” line, such as \(y \) \(\approx\) \(f(x, w, b) = w x + b, \) where w and b are the parameters of the function, in which w is called the weight and b is called bias, which doesn’t interact with the actual data \(x_i\). In order to find the “best” line, we need to define “best” and measure it. Ideally we hope \(y_i == f_i\) for every sample i, so we can use the difference or loss (\(|y_i - f_i|\), also called L1 distance) between the target \(y_i\) and predicted \(f_i\) for measurement for a single sample. When considering all the samples, we want to minimize the average loss \(\frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^m|f_i - y_i|\) for all samples (m is the number of samples). Alternatively L2 distance can be used as well and the average loss is \(L_2 = \frac{1}{m} \sum_i^m(f_i - y_i)^2,\) of course other measurement could be used as well.

Next we need to find the w and b to minimize L_2(w, b), i.e. least-squares loss, which is an optimization problem. Because of quadratic formula, we can guess \(L_2\) is has bowl-shaped appearance in 3-dimension that \(L_2\) in fact is a convex function. So based on college caculus,we can compute the partial derivative of w and b, then set them to be zero and compute the w and b (the bottom of the shape).

\[\begin{cases}\frac{\partial L_2}{\partial w} = \frac{\partial f(x, w, b)}{\partial w} = 0 \\ \frac{\partial L_2}{\partial b} = \frac{\partial f(x, w, b)}{\partial w} = 0 \end{cases}\]Above approach directly compute the best w and b based on the property of convex function, and we could ask ourselves is there other ways (say indirectly) to get w and b? Maybe we could firstly inilize w and b randomly, and then try to make it better little by little. By analogy, a blind hiker tries his best to reach the bottom of a hill, specifically try to take a step at every point.

- The first approach (Random Local Search) could be try to extend on foot in a random direction and take a step only if it leads down hill.

- Another better way is to follow the direction of steepest decend, which is the gradient or derivative of loss function at one point, and the w and b can be updated by following the best direction (gradient) and a given step (known as learning rate). Obviously the learning rate will have big impact on our algorithm; we can only get a very small progress if learing rate is too small, however when making a bigger step, we may get a higher loss because the point maybe jump to the other side of the bowl-shaped line. So we could do some research here, e.g. how to decide the learning rate (try different values with validation method), maybe we could make it dynamically. Another potential problem here is that we use all the samples to complish just one update when taking compulation complex into account. One solution is to update the parameters according to the gradient of the error with respect to one single training example only. This alogrithm is called stochastic gradient descent or online gradient decent, and batch gradient descent for previous one. SGD often gets “close” to the minimum much faster than BGD, however it may never “converge” to the minimum. Another bonus is that it is possible to ensure that the parameters will converge to the global minimum rather then merely oscillate around the minimum.

5. Genralization for high dimension data

When there are more than 1 predictor variable, we just need to change the model as \(y \approx f(x, w, b) = \sum_{j=1}^n x_j w_j + b = w^T x + b\) (w and x are vector, and n is the number of features), in fact we can make the expression more compact by setting b = \(w_0\) and \(x_0 = 1\), then \(f(x, w) = w^T x.\)

The loss \(L = \frac{1}{2m} \sum_{i=1}^m(f(x^{(i)}, w) - y^{(i)})^2\), where \(x^{(i)}\) is a vector for all features \(x_j^{(i)}\) (j=0,1, … , n) for single sample i, and \(y^{(i)}\) is the target value for this example.

Compute the gradient for all w:

- Analytic gradient, using calculus to compute the gradient directly

- Numerical gradient, which is an approximation approach based on the definition of derivatives (or gradient). The derivative of a 1-D function is the limit of the function with respect its input. When the function takes more than one parameters, the derivatives are called partial derivatives.

Update w by gradient decient: \(w_j := w_j - \alpha \frac{\partial}{\partial w_j} L(w, x)\), this regression is also called LMS standing for “least mean squares”.

Compared with two dimension model that is a line in 2-D space, we can look on n-dimension model as a n-hyperplane (subspace) in (n+1)-D space, e.g. a plane in a 3-D space.

6. Probabilistic interpretation

After understanding LMS regression above, we should again ask “Can we do better?”. I think the key or foundation of above is the least-square loss function \(L_2 = \frac{1}{m} \sum_i^m(f_i - y_i)^2\). So why this is a reasonable choice?

Because we just use f(w, x) to estimate the target y and expectation is often used for estimation, so we can interpret \(f(w, x^{(i)}) = w^T x^{(i)}\) as the expectation of estimation. So we could add an error term \(\epsilon^{(i)}\) to previous experession, as a result \(y = w^T x^{(i)} + \epsilon^{(i)}\). Because the expectation could be higher or less than the target value, we could even assume all \(\epsilon^{(i)}\) are distributed IID (independently and identically distributed) according to a Gaussian Distribution (also called a Normal distribution) with mean zero and some variance \(\sigma^2\), i.e., \(\epsilon^{(i)} \sim \mathcal{N} (0,\sigma^2)\), so \(y^{(i)} \sim \mathcal{N} (w^T x^{(i)},\sigma^2)\)

So far when given a vector w and all \(x_j\), we can compute the probability of \(y^{(i)}\) from the Gaussian Distribution. Naturally we want the maximize all the probability of \(y^{(i)}\) at the same time, and this method is called maximum likelihood. The corresponding likelihood function is

\[L(w; x) = \prod_{i = i}^m \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \, \pi} \sigma} exp({-\frac{(y^{(i)} - w^T x^{(i)})^2}{2 \sigma^2}})\]Instead of maximizing \(L(w; x)\), we can also maximize any strictly increasing function of \(L(w; x)\), naturally we can instead maximize likelihood \(l(w; x)\)

\[\begin{equation} \begin{split} l(w; x) &= L(w; x) \\ &= \log \prod_{i = i}^m \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \, \pi} \sigma} exp({-\frac{(y^{(i)} - w^T x^{(i)})^2}{2 \sigma^2}}) \\ &= \sum_{i=1}^m \log \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \, \pi} \sigma} exp({-\frac{(y^{(i)} - w^T x^{(i)})^2}{2 \sigma^2}}) \\ &= m \log \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \, \pi} \sigma} - \frac{1}{\sigma^2} \frac{1}{2} \sum_{i=1}^m (y^{(i)} - w^T x^{(i)})^2 \end{split} \end{equation}\]Because w are the only unknown parameters (assume \(\sigma\) is known), we need only to minimize the second item \(\frac{1}{\sigma^2} \frac{1}{2} \sum_{i=1}^m (y^{(i)} - w^T x^{(i)})^2\), which could be viewed as less-square loss.

When we see \(\sigma\) as the unknown parameter, we could also calculate the “best” \(\sigma\) to maximize the likelihood. I think the assumption that all the point have the same \(\sigma\) is too strong to some degree, so if they are not the same and depend on X, we can get a different loss function.

7. Get your hands dirty and have fun

- Data: I use the data from linear regression exercise from Andrew Ng’s Machine learning on Coursera.

- Setup: I choose Python (IPython, numpy etc.) on Mac for implementation, and the results are published in a IPython notebook, click here for the details

- Following is code to implement the batch and stochastic gradient decent algorithms.

import numpy as np

class LinearRegression:

def __init__(self):

self.W = None # set the weight vector

def train(self, X, y, method='bgd', learning_rate=1e-2, num_iters=100, verbose=False):

"""

Train linear regression using batch gradient descent or stochastic gradient descent

Parameters

----------

X: (D x N) array of training data, each column is a training sample with D-dimension.

y: (N, ) 1-dimension array of target data with length N.

method: (string) determine wheter use 'bgd' or 'sgd'

learning_rate: (float) learning rate for optimization

num_iters: (integer) number of steps to take when optimization

verbose: (boolean) if True, print out the progress when optimization

Returns

-------

losses_history: (list) of losses at each training iteration

"""

dim, num_train = X.shape

if self.W is None:

# initilize weights with small values

self.W = np.random.randn(1, dim) * 0.001 # [1, D]

losses_history = []

for i in xrange(num_iters):

if method == 'sgd':

# randomly choose a sample

idx = np.random.choice(num_train)

loss, grad = self.loss_grad( X[:, idx, np.newaxis], y[idx, np.newaxis])

else:

loss, grad = self.loss_grad(X, y)

losses_history.append(loss)

# Update weights using matrix computing (vectorized)

self.W -= learning_rate * grad

if verbose and i % (num_iters / 10) == 0:

print 'iteration %d / %d : loss %f' %(i, num_iters, loss)

return losses_history

def predict(self, X):

"""

Predict value of y using trained weights

Parameters

----------

X: (D x N) array of data, each column is a sample with D-dimension.

Returns

-------

pred_ys: (N, ) 1-dimension array of y for N sampels

"""

pred_ys = self.W.dot(X)

return pred_ys

def loss_grad(self, X, y, vectorized=True):

"""

Compute the loss and gradients

Parameters

----------

The same as self.train function

Returns

-------

a tuple of two items (loss, grad)

loss: (float)

grad: (array) with respect to self.W

"""

if vectorized:

return linear_loss_grad(self.W, X, y)

else:

return linear_loss_grad_naive(self.W, X, y)

def linear_loss_grad(W, X, y):

"""

Compute the loss and gradients with weights, vectorized version

Parameters and Returns are the same as LinearRegression.loss_grad, except including W as parameter

"""

# vectorized implementation

num_train = X.shape[1]

f_mat = W.dot(X) # [1, D] * [D, N]

diff = f_mat - y # [1, N] - [1, N]

loss = 1.0 / (2 * num_train) * np.sum(diff * diff) # [1, N] * [N, 1]

grad = 1.0 / num_train * diff.dot(X.T) # [1, N] * [N, D]

return (loss, grad)

def linear_loss_grad_naive(W, X, y):

"""

Compute the loss and gradients with weights, for loop version

"""

num_train = X.shape[1]

loss = 0

grad = np.zeros_like(W) # [1, D]

for i in xrange(num_train):

sample_X = X[:, i] # a vector

f = 0

for j in xrange(W.shape[1]):

f += sample_X[j] * W[0, j]

diff = f - y[i]

loss += diff ** 2

for j in xrange(W.shape[1]):

grad[0, j] += diff * sample_X[j]

loss = 1.0 / (2 * num_train) * loss

grad = 1.0 / (num_train) * grad

return (loss, grad)

8. Summary

- We all should keep it in mind that linear regression is based on the assumption that the true model is linear or close to linear, so we should be very careful if we don’t known the true model in advance.

- Most people use least square error to indicate the loss of the linear model and it can be interpretated from probabilistic aspect, i.e., assuming that the errors are distributed IID according to a Gaussian Distribution, the probability of y based on x (

p(y|x)) for all the samples can be maximized to minimize the least square error. Of course, we can choose other loss function as long as it makes sense to measure the agreement between the predicted scores and the ground truth value. - We can use normal equation \(W = (X^T X)^{-1} X^T y\) to compute W directly based on calculus, however it works slow when n is large, instead, gradient decent algorithm is more practical based on the bowl-shape of loss function. The basic idea is to reduce the loss step by step.

- For implementation, it is critical to use matrix calculation. Not only can it speed up the computation, but also can make code simpler and conciser when compared to naive loop version.

9. Reference and further reading

- Andrew Ng’s Machine learning on Coursera

- Andrew Ng’s machine learing notes on Stanford Engineering Everywhere (SEE)

- Machine Learning Module in the University of Nottingham